The impulse to compare the novel coronavirus to the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 is understandable. But as we move toward re-opening the economy, I’ve seen a couple of memes floating around that gave me pause. And if I was wondering about them, I figured others might be too. So I did some research, and put together a bit of history on the Spanish Flu (and other thoughts). Here we go:

The History of the Spanish Flu

Until yesterday, everything I knew about the Spanish Flu came from watching the Disney movie Goodbye Miss Fourth of July. Maybe you’ve seen it. Anyway, it captured the difficulty of that time well. The numbers of infected people. How the main character could only meet her new baby sister through the window because she’d been nursing the sick.

But that movie is probably not the most effective way to explore the events of that outbreak. So I did a bit of research on history sites. I looked for articles originally written before the COVID-19 outbreak and perhaps updated during our quarantine.

Here’s what I found:

Fact: The Spanish Flu did kill more people than WWI, but not in the final months of 1918. Its final death total (of 20-50 million people worldwide) was over a two-year, three-wave span.

Fact: The Spanish Flu did not start in Spain. It hit Spain hard and only Spanish journalists were not blocked by wartime news limits. So if you wanted to know about it, you read the Spanish papers.

Fact: The original outbreak in early 1918 was a mild form of influenza, a three-to-five day illness from which most people recovered. It hit hardest those who are most susceptible to the flu—the young, the old, and the infirm. But it was also easily transmissible and spread quickly.

Fact: Sometime after the spring outbreak, the virus mutated somewhere in Europe. Then we carried its new form all over the world with the mobilized armies and their required supplies. The new version could kill within 24 hours of infection and affected even the typically healthy 20-50 year old population. In cases, a person could go to bed feeling fine, wake up feeling sick, and die on the way to work.

Comparing 1918 and 2020

That is, of course, the briefest look at the history of that worldwide disaster. Especially now, we should read up on a disease that caused more destruction than even the bubonic plague of the Middle Ages.

But how does the Spanish Flu help us? Facing our own pandemic, is the Spanish Flu a good comparison?

Yes and no.

Yes, because it’s the closest historical pandemic that we can study and learn from.

No, because it really isn’t an exact match, so we need to be careful about both what we claim about that time and conclude (based on it) about our own.

The Impact of Social Media

This week, I started seeing pictures about the Spanish Flu on social media. And they were concerning enough to me that I started reading on my own.

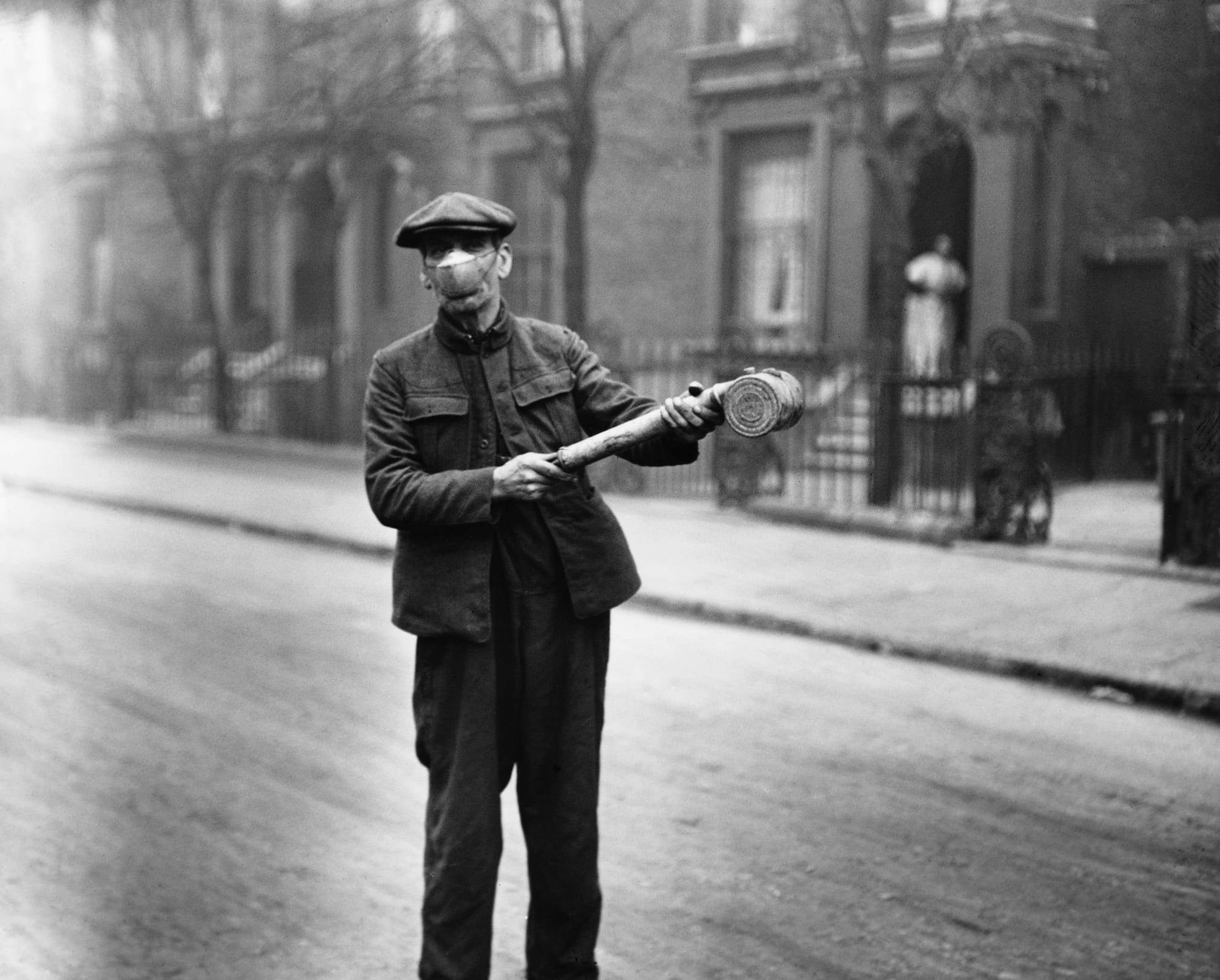

Twice in the last two days, I’ve seen black-and-white images with an assertion (without any sources or support) about the pandemic of 1918 and leading to an “obvious” conclusion.

The first one claimed that the final months of 1918 saw more deaths than WW1, which seemed a remarkable claim. That was the reason I went looking on the history sites in the first place (see above). The second one said that easing the quarantine in Philadelphia to welcome soldiers home caused the fall’s massive death tolls.

And in both cases, I was concerned, not about the conclusions drawn (okay, a little bit about the conclusions drawn) but more with how many people would see and trust those memes without doing any checking of their own.

Which is always a problem. Because discernment, the ability to assess truth and ask good questions, is vital all the time. But especially so when things are uncertain and we jump to conclusions which we then guard with our lives.

Other Thoughts on the Spanish Flu

So once I’d read over the history of that first pandemic, I read some articles about the Spanish Flu in comparison to the novel coronavirus. And as always, the truth is more complex than a social media post can cover.

So here are my other thoughts on the Spanish Flu.

First, though similar, they are not an equal comparison.

Both viruses were brand-new, unknown entities when they emerged into the human population. They both attack the lungs (though in slightly different ways). Both have been able to kill a large number of people in a short amount of time.

But that’s really where the comparisons end. The novel coronavirus is worse than the early Spanish Flu but much less severe than the mutated, virulent strain that emerged later.

Second, our ability to respond to a new virus is immensely better than it was in 1918. Then the medical community had been separated and reduced due to war. They didn’t have microscopes capable of seeing viruses until the 1930s. And the medicines available then were simply ineffective or more dangerous than the actual disease. (They prescribed toxic doses of aspirin which, most likely, exaggerated to the death toll.)

We now have seventy years of vaccine and anti-viral technology to use as a basis for fighting this disease. In 2020, we have respirators, emergency equipment, and various drugs and clinical trials already providing potential treatments to mitigate, though not cure, the novel coronavirus. We have a technological advantage, as well as a host of immediate communication methods, that simply didn’t exist in 1918.

Those one hundred years of knowledge and technology means we are not blindfolded and handcuffed as they were during the Spanish Flu pandemic. And that is a significant difference.

Second, we cannot take “what we should do now” directly from the pages of history.

The second meme claimed, “They lifted the quarantine for a parade, and it killed them all.” And the conclusion was

“So we can’t lift our social distancing measures yet either.”

But that isn’t the whole story. In 1918, they did many of the same social distancing measures we are using. Stay-at-home orders, quarantines, face masks, and other things worked then, and they are working now. That’s good. (Of course, the mass movement of troops and supplies for war worked against them, too.)

And as we reopen, we will go back to spreading germs, harmless and otherwise, because that’s how germs and human interaction work. Some of those germs will now be the novel coronavirus, and more people will get sick. That’s true.

But it was not the coming back together that caused the hell-on-earth of those last three months of 1918. It was the newly mutated, highly-virulent strain of the virus that did that. Because no one knew it had mutated. The novel coronavirus has not (yet) mutated, though it is not out of the question that it can. Still, with all the scientists studying this virus, it is nearly impossible to miss mutations or be unable to respond accordingly.

The decision to lift—or not—a social distancing orders cannot be based entirely on what happened in 1918. It’s too simplistic to say “In 1918 they attended a parade and died.” And using the Spanish Flu pandemic as a means to scare people into staying home is not helpful either. Scare tactics are never discerning.

Final Thoughts

The point of this article isn’t to say we should or should not maintain social distancing orders. It isn’t to convince you what is the best course of action in 2020.

But the Spanish Flu pandemic, while historically helpful, is not the best guide for us to use as we decide what is best for our neighborhoods, states and country as a whole.

Their situation was much more complex than the memes indicate. Ours is much more informed than theirs was. And while we cannot stop the entire tragedy of losing lives to the novel coronavirus, we can do and are doing the best we can with the information we have.

I’m sure you have other thoughts on the Spanish Flu or on the current pandemic we face. Feel free to leave thoughtful comments or questions below. Together, as we fight or think or support our communities and leaders, I am still convinced we will come out of this challenge better than we were before.